Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael Alexander‘The Girl in the Picture’: Survivor of war teaches peace

By NICHOLE GOLDEN, Staff Writer | Published November 7, 2013

ATLANTA—An entire generation instantly recognizes the image of an unclothed Vietnamese girl running toward the camera in terror after a bombing at her village.

Taken by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut in June 1972, the black and white photograph became one of the most iconic pictures from the Vietnam War.

While speaking to a small group of Marist students and staff in a more intimate setting, Vietnam War survivor Kim Phuc Phan Thi shows some of the scars she still bears from a 1972 napalm bomb attack leveled upon innocent civilians in her Vietnamese village, Trang Bang. Kim was only 9 years old when she was severely burned over half her body. Today she travels around the world telling her story, while conveying a message of forgiveness and peace. Photo By Michael Alexander

Napalm bombing survivor Kim Phuc Phan Thi, the girl from the picture, visited Marist School in Atlanta on Oct. 22. Phuc asked students there to help spread a message of peace and forgiveness.

Dressed in a traditional Vietnamese dress or áo dài, Phuc delivered a soft-spoken yet mighty testimony.

“I came through the fire and I am blessed to be here,” said Phuc.

Students, faculty and guests gathered in the school’s Centennial Center to hear Phuc’s presentation of “Love, Hope and Forgiveness.”

Kim Phuc was 9 years old when the attack occurred. She and her family had been hiding in a Buddhist pagoda in Trang Bang and she was severely injured with third-degree burns over much of her body. Phuc’s clothing was burned off by the intense heat of napalm.

A sticky gel-like substance, napalm was used in incendiary bombs and flamethrowers and contained gasoline and soaps.

Ut captured the scene of Kim Phuc and other children fleeing down a road and then immediately drove her and others to a South Vietnamese hospital. His photograph won a Pulitzer Prize.

Phuc underwent 17 surgeries in 14 months before returning home. She is one of few napalm victims to survive burns as the substance can reach temperatures of more than 1,500 F. Phuc’s infant cousins died in the attack.

Phuc, who now lives in Canada with her husband and teenaged sons, told Marist students that patiently practicing daily prayer helped her to forgive.

“It wasn’t easy,” she said. “All of you can do it here, too.”

Army officer asks her forgiveness

Her presentation included a clip from a Canadian documentary featuring her 1996 visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. Army Capt. Ron Gibbs, who served on the board of the memorial fund, invited her to a Veterans Day event.

Phuc told the audience at the memorial that if she could meet with the pilot responsible for the attack, she would forgive him, saying we “cannot change history,” but should all try to do good things.

Capt. John Plummer was there that day. “I knew also that extended to me,” said Plummer in the documentary. He believes he helped coordinate the bombing and said the intended targets were nearby enemy bunkers, not the village.

When Plummer read about the bombing in the newspaper Stars and Stripes, he said it was like being “hit with a baseball bat.”

In her right hand Kim Phuc Phan Thi holds a glass of coffee, and in her left hand she holds a glass of water. Phuc used the coffee to symbolize the darkness in her heart before she overcame the challenge to forgive, and the water represents her heart after she learned how to forgive those who had hurt her. She gave the example during an Oct. 22 presentation at Marist School’s Centennial Center. Photo By Michael Alexander

Upon his return home from Vietnam, Plummer struggled with alcoholism and broken marriages.

He said he knew his struggles would continue, “until I reconcile with Kim somehow.” He passed a note to a National Park Service policeman at the memorial, hoping to get the chance to meet with her after the ceremony. A friend helped facilitate the meeting.

“It was really touching,” said Plummer in the documentary. “The entire world has lifted off my shoulders.” Now a Methodist minister, Plummer said he knew Kim would see his sorrow and know it was from his heart.

“We became good friends,” said Phuc of her relationship with Plummer. “It was truly reconciliation.”

The path for Phuc has been long though, and several things have helped in healing, including her family, her relationship with God, and seeking asylum in Canada.

After her surgeries, Phuc returned to her village, suffering from pain and severe headaches. Later, the local government removed her from school, forcing her to serve as a symbol of the state.

In 1986, Phuc went to study in Cuba and met and married Bui Huy Toan. Phuc and her husband sought political asylum in Canada during a wedding trip stopover in Newfoundland.

She knew nothing about Canada, but the newlyweds immersed themselves in the culture, learning English, volunteering, working and seeking education. They used food subsidy not to buy food, but to ride a bus to school.

“They adopted us,” she said of the Canadian people. Her life there is “so peaceful and wonderful,” Phuc said.

Phuc also talked about how her sons Thomas and Stephen, ages 16 and 19 respectively, helped her in healing emotionally.

When Thomas was just learning to speak, he noticed his mother’s scarred arm while she was wearing a short-sleeve shirt. Thomas asked, “Mom hurt?” Then the toddler kissed his mother’s scars.

“It really touched my heart,” said Phuc.

“They pray for me,” and through FaceTime, she can talk with them when traveling.

Phuc, who takes more than 40 trips a year to speak about peace and the work of her international foundation, uses the technology to keep in touch.

“You still have to share your mom with the world,” she tells her sons.

‘Forgiveness is a choice’

The Kim Foundation International is a nonprofit organization that funds medical care and psychological assistance for child victims of war. In 1997, the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization named Phuc a Goodwill Ambassador of Peace.

Phuc showed the Marist students pictures of the foundation’s current project—an endeavor to build a pediatric and corrective surgery recovery ward in Uganda, where the people have experienced two decades of war, disease and high HIV rates.

Marist School eighth-graders (l-r) Meg Fennelly, Mae Mae Utsch and Molly Sikes listen as Vietnam War survivor Kim Phuc Phan Thi shares her story during a school-wide assembly inside the Centennial Center, Oct. 22. Photo By Michael Alexander

During the school assembly, Phuc discussed the different kinds of war that occur on a personal level or the “bombs that have exploded in your heart.” Financial problems, illness or unemployment create struggles and hurt in families. “Forgiveness is a choice,” she said.

Phuc, who became a Christian in 1982, used a glass filled with dark coffee to depict herself prior to learning to forgive. The dark liquid has to be poured out of the heart, she said. A crystal clear glass of water represents what forgiveness can bring.

During a question-and-answer session, one student asked about her health. She talked about the condition of her burned skin. “It’s like plastic,” she said. Because she has no pores, keeping her body temperature regulated is an issue.

“I never focus on the pain,” said Phuc. She added that when tragedy comes it’s easier to be bitter.

Although she still carries the physical scars, “my heart is healed,” said Phuc.

Following the assembly, Phuc spent time with representatives of the school Mosaic group, the Emmaus board, and Eucharistic ministers. The Mosaic group organizes programs that promote understanding of other cultures and diversity, while the Emmaus board plans spiritual retreats for juniors and seniors.

“I thought it was amazing,” said senior Briana Bell about the presentation.

Senior Christina Clodomir also felt a connection to Phuc’s message, calling it very “relatable.”

Student Julian Clark said Phuc’s story makes daily problems encountered by others “pale in comparison.” Clark wondered aloud where she gets her courage to speak about the past.

“Faith is what it boils down to,” he said.

‘New way’ to see the picture

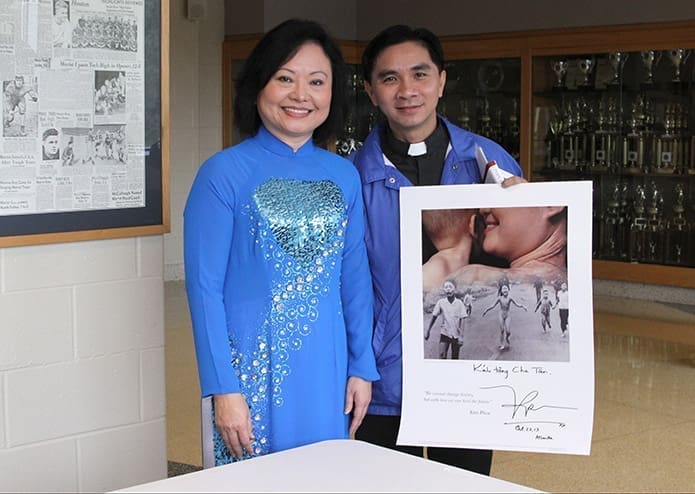

Jesuit Father Tan Pham, from Transfiguration Church in Marietta, grew up in Saigon, just a few miles from Trang Bang. Father Pham joined the group and called Phuc’s message “very powerful.” Father Pham came to the United States in 1982 and had long wanted to meet her.

“You can be my ambassadors,” Phuc told the smaller group of students, who listened intently to her insights.

Following a presentation to the entire student body, Kim Phuc Phan Thi speaks with a smaller group of students from campus organizations like the Emmaus board, the Mosaic diversity group and the Eucharistic minister board. Phuc further informed the students that her life was changed forever in 1972, but she did not allow war to kill her life, hope or future. Photo By Michael Alexander

Phuc discussed whether physical or emotional wounds are more difficult to heal. She said the emotional wounds are more challenging.

“You can see the power of napalm,” she said. “It can burn my body. It cannot burn my soul.”

Phuc said she is not an overly religious person, but she has a deep relationship with Jesus.

“The more I pray, the more peace I have,” she explained.

Part of her struggle of being the “little girl in the famous picture” was that her own government wanted to use her life and the picture.

Phuc gave three Ds—desire, determination and discipline—for the students to follow in attaining dreams. She told them to have good desires, to be determined in reaching goals, and to discipline themselves.

Phuc encouraged them to worry less, as no one can control life or death, to forgive hurts, to live simply, to give more and expect less.

“We cannot change history, but with love we can heal the future,” is the message on a poster that Phuc created using the famous photo and a newer image.

“I really want to give you a new way of looking at my picture,” she told the students.

Friend Anne Bayin took a photograph of Phuc holding Thomas when he was a baby. Kim Phuc is smiling and Thomas is facing the other direction while listening to his mother, as if looking toward the future. The space between the mother and child forms a heart. Ut’s well-known photo is there, but she urges those viewing the collage not to see the pain and fear, but rather the child “crying out for peace” and the hope of a mother’s smile.

“I came from war, and now I value peace,” she said.

Individually everyone must practice peace whether they are a world leader or an everyday person, said Phuc.

“People talk about peace, but they don’t know what they are talking about. … It’s in here,” she said, pointing to her heart.

Phuc signed two posters, one for Father Pham and one for Marist School to keep. She gave a copy of Denise Chong’s book, “The Girl in the Picture,” to one of the students.

“So you will be my ambassadors,” she told the group.